7주년 노벨상 7주년 기념 기념연설 - 버틸 린트너 기자

본문

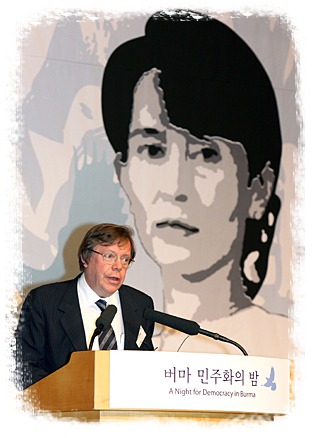

'버마 민주화의 밤' 기념 연설

버틸 린트너(Bertil Lintner)

1917년 불교 사원이나 수도원을 출입할 때 영국 관리는 신을 벗지 않아도 된다는 발표가 있자, 버마 국민들은 영국 식민 통치자들에 맞서 전례 없는 항거를 했습니다. 서방세계 사람들에게는 그와 같은 저항이 이상하게 보였을지 모릅니다만, 버마인들에게는 그들 종교에 대한 근본적인 모욕이었습니다. 그 신발 사건' 은 1920년대 버마의 전 국가적 동요를 일으켰고, 버마에서 식민 통치의 끝을 알리는 출발점이 되었습니다.

역사는 되풀이되고 있습니다만 상황은 훨씬 더 가혹해졌습니다. 버마 군인들은 9월 말 승려들을 무력 진압하던 중 군화를 신은 채 성스러운 예배당을 침입했을 뿐 아니라, 사원에서 금으로 된 물품과 TV, 휴대폰, 선풍기 등을 훔쳤습니다. 승려들은 구타당하고 체포되었으며 심지어 살해되기도 했습니다. 군대가 수도원을 침입한 것은 버마 군사 통치의 끝을 알리는 출발점으로 봐야 한다고 생각합니다. 버마의 군부 통치자들은 그들의 정당성이 무엇이건 간에 이제 그것을 잃었으며 예전과 같이 버마를 통치할 수는 없을 것입니다.

그러나 문제는 어떻게 군부 통치를 민주 질서로 대체할 것인가 하는 것입니다. 1962년~1972년 10년 사이 전 세계적으로 64개의 군사 정권이 들어섰는데, 대개 민간 정권을 전복시키고 들어선 이들 중 오늘날까지 권력을 장악하고 있는 곳은 둘 뿐입니다. 하나는 카다피가 1969년 정권을 잡은 리비아이고, 다른 하나는 버마입니다. 1962년 버마 군대는 민주적으로 선출된 우 누(U Nu) 총리가 이끄는 정부를 전복시킨 이래 다양한 모습으로 권력을 장악해 왔습니다.

정권을 장악한 수년 동안 버마 군대는 국가 내 국가, 즉 군인과 그 가족 및 부양인들은 태국이나 인도네시아의 군인들도 누리지 못한 특권적 지위를 누리는 사회가 되었습니다. 반면 태국과 인도네시아에서는 가장 암울한 군사 독재 하에서도 어느 정도의 다원주의는 수용되었습니다.

버마 군대가 1962년 정권을 장악했을 때 당시 육해공군 수는 104,200명이었습니다. 그 수는 1976년 140,000명, 1985년 160,000명으로 늘어났고, 1988년 민중 봉기 당시에는 육군만 180,000명, 삼군을 합치면 거의 200,000명까지 늘어났습니다. 오늘날 육해공군 규모는 약 400,000에 달하는 것으로 추산되며, 버마의 근대사를 통틀어 그 어느 때보다 훌륭한 장비를 갖추고 있습니다.

군대가 계속해서 결속하고 버마 국민들로부터 분리되어 있는 한 어느 것도 변하지 않을 것입니다. 그러나 아직까지 군대 내에 분열이 있다는 보고는 없습니다. 그들이 남용해온 권력, 특권, 그 동안 저지른 악행을 감안해 볼 때, 버마 군대는 개방과 투명성을 허락함으로써 얻을 것이 하나도 없습니다. 모든 것을 잃을 뿐입니다. 해외에 기반을 두고 있는 야당 세력들은 “대화”와 “국가적 화해”라는 말을 좋아합니다만, 자신들 외에는 누구와도 얘기하지 않는 버마 군대에는 큰 연관성이 없는 대중적 문구에 지나지 않습니다. 랑군에 위치한 한 서방세계 외교관은 다음과 같이 얘기했습니다: “그들은 서로 뭉치지 않으면(hang together) 각자 교수형을 당할까(hang) 두려워하고 있다.”

버마 최고 통치자들은 민주주의를 기존 질서에 대한 위협으로 보고 있으며, 자신들의 권력이나 특권을 앗아가는 협상을 하지 않을 것입니다. 그리고 권력을 유지하기 위해 심지어 승려들을 살해하고 수감시키는 등 무엇이라도 할 용의가 있다는 것을 계속 보여 주었습니다.

변화는 군대 내에서도 좀 더 진보적이며 특권을 덜 누리고 있는 군 장교들이 최고 장군들에 대항하는 움직임을 결심할 때에만 현실적으로 가능해질 것입니다. 그러나 주류 군대의 지위에 대한 도전이 감지되면 심각한 저항이 있을 것이므로 결과는 폭력적이거나 심지어는 내전으로 귀결될 수도 있을 것입니다.

버마는 1962년 이래 진정한 민간 정부가 수립된 적이 없기 때문에 행정적 능력이나 경험 있는 사람이 부족합니다. 민주화 운동의 상징인 아웅산 수지 여사는 넬슨 만델라가 남아프리카 자유의 상징이 된 것처럼 국가적 리더의 역할을 맡을 수 있을 것입니다. 여사가 군부 지도자인 탄 쉐 장군보다 지도자적 자질을 더 많이 가지고 있는 것은 분명하겠습니다만, 그러나 그녀 주변에는 능력 있는 인물이 부족합니다. 그녀가 이끌었던 민족민주동맹(National League for Democracy)은 만델라가 수감 중이었을 때에도 다른 능력 있는 지도자들과 함께 대규모 민주화 운동을 벌일 수 있었던 남아프리카의 아프리카민족회의(African National Congress)가 아닙니다.

NLD는 1990년 총선에서 485석 중 392석을 차지하며 압승을 거뒀습니다만, 의회는 한 번도 소집되지 못했습니다. 대신 수십 명의 의원들이 체포되었고, 혹은 인접국인 태국이나 인도 등으로 피했습니다. NLD는 한 때 강했으나 지금은 1980년대 말, 1990년대 초 NLD의 암울한 그림자에 지나지 않습니다. 초기에는 젊은 운동가들이 많았으나 지금은 대부분 수감됐거나 버마를 떠났습니다.

최근 몇 년 사이 버마에서 등장한 유일한 민간 세력은 소위 “88 세대 학생 그룹”이라는 것인데, 이는 1988년 민중 항쟁을 이끈 베테랑들이 작년 8월 결성한 것입니다. 1989년 3월에 체포되었다가 2005년 11월에서야 석방된 학생 리더 민 고 나잉(Min Ko Naing)은 16년 가까운 시간을 독방에서 보냈습니다. 그와 그의 단체는 8월 19일에 있었던 연료유 가격 인상에 반대하는 첫 번째 거리 시위 조직에 일조했으며, 이는 이후 대규모 운동을 촉발했습니다. 그러나 민 고 나잉(Min Ko Naing)과 150여명에 달하는 동료 운동가들은 첫 번째 시위가 일어난 지 며칠 만에 다시 체포되었습니다.

분명 민간 야당 세력은 현 정권 붕괴 시 초래될 권력 공백을 메우거나 혼자 새로운 정부를 구성할 능력이 부족합니다. 국가를 망치고 사원을 모독한 장군들은 어떻게 해야 하겠습니까? 최근의 폭력 진압 후 그들을 용서하는 것은 불가능할 것입니다. 그러나 그들을 기소한다면 그 숙청 과정은 어느 정도 하부 단계까지 진행되어야 할까요? 아니면 최근 랑군의 폭력 진압 후 미 정부 대변인이 제안한 것처럼 최고 지도자들을 사면해 주고 중국 등지로 망명 보내야 할까요?

설령 군대 내에 보다 젊고 개혁 지향적인 장교들이 있다 하더라도 그들은 지극히 행동을 조심해야 할 것입니다. 그러나 그렇다 하더라도 버마의 유일한 희망은 군대 내 개혁적인 장교들과 민주화 운동 세력이 만날 때에만 가능할 것입니다. 군부가 무너질 때 그들은 함께 국가를 건설할 수도 있을 것입니다. 그것이 또 다른 수많은 문제를 초래할 수도 있겠지만 말입니다.

"SPEECH"

By Bertil Lintner

Nothing galvanized the Burmese nation against its colonial masters more than a proclamation in 1917 saying that British officials would not have to remove their shoes when entering Buddhist temples, pagodas and monasteries. It may sound strange to Westerners that this caused such an outcry, but, to the Burmese, it was the ultimate insult against their religion.

The "Shoe Issue" dominated nationalist agitation in the 1920s, and it marked the beginning of the end of colonial rule in Burma. Today, history is repeating itself, but in a much more brutal way. During the crackdown on the Buddhist clergy in late September, heavily-armed Burmese government soldiers did not only tramp into sacred places of worship with their army boots on, but they also stole from the monasteries gold objects, televisions, mobile phones, fans and other items. Monks were beaten, arrested and some were even killed. The army's stampede into the monasteries, I think, should be seen as the beginning of the end of military rule in Burma. The country's military rulers have lost whatever legitimacy they had left, and will not be able to govern the country like before.

But the question is: how will military rule end and a democratic order replace it? During the decade 1962 to 1972, there were 64 military takeovers through out the world, most of them overthrowing civilian governments, but only two of them remain in power today. One of them was Libya, where Mohammar Khadaffy seized power in 1969. The other was Burma. In 1962 the military overthrew the democratically elected government of prime minister U Nu, and have been in power under various guises ever since. During its many years in power, the Burmese military has become into a state-within-a-state, a society where army personnel, their families and dependents enjoy a position far more privileged than their counterparts ever had in, for instance, Thailand and Indonesia. In both those countries. some degree of pluralism was always accepted even during the darkest years of military dictatorship.

When the emerging state-within-a-state gobbled up the state in 1962, there were 104,200 men in all three services. That rose to 140,000 in 1976, 160,000 in 1985, and, at the time of the 1988 uprising, 180,000 in the army and nearly 200,000 in all three services. Today, the strength of the three services is estimated at 400,000, and they are much better equipped than at any time in Burma's modern history, mainly due to massive procurement of arms from China. Nothing is going to change as long as the military remains united and isolated from the population at large, which it is today, but there have so far been no credible reports of splits within the military. Given the abuse of power, their privileges and the atrocities they have committed, the Burmese military has everything to lose and nothing to gain from allowing more openness and transparency.

Foreign-based opposition groups like to talk about "dialog" and "national reconciliation", but these are no more than popular buzzwords of little relevance inside Burma, where the military talks to no one but itself. A Rangoon-based Western diplomat once put it to me quite bluntly: "They fear that if they don't hang together, they'll hang separately."The top leaders see democracy a threat to the existing order, and they are not going to negotiate away their power and privileges - and they have shown time and again that they are willing to do anything to cling on to power, even killing and imprisoning Buddhist monks.Only if a group of more liberally-minded, and less privileged, army officers decide the move against the top generals can change be a reality, but given the resistance that could be expected to any challenge to the status from main-stream military, the outcome could be violent, and perhaps even result in civil war. And because the country has not had a truly civilian government since 1962 it lacks people with administrative skills and experience.

Aung San Suu Kyi, the icon of the pro-democracy movement, would most probably be able to assume the role of a national leader in the same way as Nelson Mandela became the symbol of freedom in South Africa. But although she certainly has more leadership qualities than, for instance, junta leader Than Shwe, she lacks competent people around her. Her National League for Democracy, NLD, is not the African National Congress, which had many able leaders and could function as a mass movement even though Mandela was in prison.

The NLD won a landslide victory in the 1990 parliamentary election, capturing 392 out of 485 contested seats. But the elected assembly was never convened; instead, scores of MPs elect were arrested and others sought refuge in neighbouring Thailand and India. Today, the once mighty NLD is only a bleak shadow of what it was in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Most young activists - and there were many in the beginning - have been imprisoned, cowed into submission or fled the country. The only other civilian force to have emerged in Burma in recent years is the so-called "88-Generation Students' Group", which was set up in August last year by veterans of the 1988 uprising. Led by Min Ko Naing, a student leader who was arrested in March 1989 and released only in November 2005, having spent nearly 16 years in solitary confinement. He and his group played some role in organising the first street protests against a hike in the price of fuel on August 19, which ignited the mass movement that followed. But Min Ko Naing and perhaps as many as 150 of his fellow activists were arrested within days of the first demonstration.

Clearly, the civilian opposition does not have adequate capacity to fill the power vacuum that the collapse of the present regime would produce, and to form, alone, a new government. And what should be done with the generals, who have ruined the country and desecrated the monasteries? A pardon is not possible after their most recent outrage, but, if the leading generals are prosecuted, how deep down in the ranks should the purge go? Or should the top leadership be granted amnesty and sent into exile in China, as spokesmen for the US government suggested after the recent crackdown in Rangoon? And if there indeed are any younger-reform minded officers within the armed forces, they must be keeping an extremely low profile.

But even so, Burma's only hope is a meeting of minds between elements of the armed forces and the pro-democracy movement. Together, they may be able to hold the country together when the junta falls. But that will only be the beginning of a host of other problems.Ends