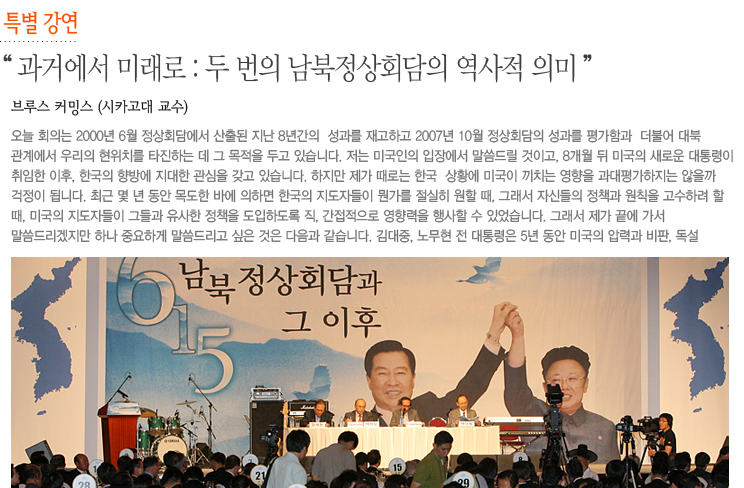

8주년 6·15 남북정상회담 8주년 기념식 - 특별강연 ( 브루스 커밍스 교수 )

본문

오늘 회의는 2000년 6월 정상회담에서 산출된 지난 8년간의 성과를 재고하고 2007년 10월 정상회담의 성과를 평가함과 더불어 대북 관계에서 우리의 현위치를 타진하는 데 그 목적을 두고 있습니다. 저는 미국인의 입장에서 말씀드릴 것이고, 8개월 뒤 미국의 새로운 대통령이 취임한 이후, 한국의 향방에 지대한 관심을 갖고 있습니다. 하지만 제가 때로는 한국 상황에 미국이 끼치는 영향을 과대평가하지는 않을까 걱정이 됩니다. 최근 몇 년 동안 목도한 바에 의하면 한국의 지도자들이 뭔가를 절실히 원할 때, 그래서 자신들의 정책과 원칙을 고수하려 할 때, 미국의 지도자들이 그들과 유사한 정책을 도입하도록 직, 간접적으로 영향력을 행사할 수 있었습니다. 그래서 제가 끝에 가서 말씀드리겠지만 하나 중요하게 말씀드리고 싶은 것은 다음과 같습니다. 김대중, 노무현 전 대통령은 5년 동안 미국의 압력과 비판, 독설 속에서 북한 포용정책을 견지해왔고, 결국 부시 정부가 180도 태도를 전환하면서 포용정책을 수용함에 따라 그 정당성을 입증할 수 있었다는 것입니다. 이런 결과가 나온 이유는 아직 분명히 밝혀지지 않은 미스터리이지만 어쨌든 현실로 나타난 것입니다.

최근 한국의 새 정부는 미국의 환심을 사기 위해 부시 대통령조차도 강경 노선을 포기해버린 지금 대북 강경 정책을 취하면서, 미국 정부를 염두에 둔 듯 "잃어버린 10년"이 대한 이야기를 하고 있습니다. 또한 부시의 지지도가 그렇게 낮아진 이유에 (현대 투표제 실시 이후 최저 지지율을 기록했습니다.) 대한 숙고도 없이 또는 차기 미 대통령은 공화당 출신이 아닐 가능성을 고려해 보지도 않은 채 그러한 모습을 보이고 있습니다.

제 말씀이 당파적으로 들릴 수도 있겠습니다만, 어떤 정치 지도자는 현실을 직시하지만 어떤 정치 지도자는 그러지 못하는 경우가 있는데, 이것이 바로 그런 경우에 해당된다고 생각됩니다. 전 세계인들이 이 실패한 부시 행정부가 워싱턴을 떠날 날을 손꼽고 있지만 청와대만은 그렇지 않은 것 같습니다.

2000년 정상회담

우리는 2000년 6월 평양 정상 회담으로 정점을 이루었던 김대중 대통령의 중대한 대북 정책 변화를 기념하기 위해 모였습니다. 그 회담에서 두 정상은 1945년 분단 이후 처음으로 악수를 나누었습니다. 역사학자로서 저는 서울이 그 어떤 곳보다 즉각적으로 받을 수 있는 큰 위협에 직면했음에도 불구하고, 김대중 대통령이 대한민국과 미국의 어떤 대통령보다 대북 정책에 많은 변화를 이루어냈다고 판단합니다. 1998년 2월 대통령 취임식에서 김대중 대통령은 "적극적으로 화해와 협력을 모색할 것"을 약속하셨고, 북한의 대 미국, 대 일본 관계를 개선하고자 하는 노력을 지원하겠다고 선언하셨습니다. 이는 친선 화해의 기미는 강하게 일축해왔던 전임 대통령들과는 완전히 다른 입장이었습니다. 김 전대통령은 "흡수 통일"(전임 대통령들의 실질적 정책이었다)을 분명하게 거부했고 평화적 공존 기간을 연장하고, 통일을 2-30년 후로 연기한다는 것으로 한국 정부의 입장을 밝혔습니다. 1998년 6월 미국 방문에서 김 전 대통령은 대통령으로서는 한국 최초로 미국의 대북 경제 봉쇄 정책 철폐를 요구하였습니다. 북한은 김 전 대통령의 의지를 시험하기 위해 1년을 지켜보았고, 그 동안 잠수정 몇 척과 몇몇 침입자 시신들이 한국 해변에 나타나기도 했습니다. 이는 강경론자들이 남북 관계 진척을 어렵게 하려 할지도 모른다는 추측이 가능한 부분입니다. 그러나 1999년 중반에 이르러, 북한은 김 전 대통령의 "햇볕 정책"이 남한 대북 입장 선회라고 판단했다는 사실이 명확해 졌습니다. 미국 정부에 대한 북한의 태도 역시 변화하기 시작했습니다. 주한미군 철수 입장을 오랫동안 견지해 왔었지만, 적어도 일부 북한 지도자들은 국제적인 힘의 역학 관계 변화 (특히 강력한 일본과 강력한 중국)를 헤쳐 나가고, 경제적 난국을 타개할 수 있도록 주한미군의 주둔이 지속되어야 한다고 생각하는 것처럼 보였습니다.

남북 관계의 문제에 대한 김 전대통령의 오랜 연구와, 북한이 붕괴하지 않을 것이며 따라서 우리가 원하는 대로 바꾸어 나가는 것이 아니라 "있는 그대로" 다루어야 한다는 인지에서 햇볕 정책이 태동하였습니다. 원숙미의 가치는 어떤 예측이 올바른 방향으로 나갈 수 있는지 여부를 판단할 수 있다는 데 있습니다. 1989-90년 동유럽 체제가 붕괴된 이후, 많은 전문가들이 북한의 붕괴를 예견했습니다. 하지만 저는 다음과 같은 세 가지 이유에 근거하여 북한이 붕괴되지 않을 것이라고 주장하였습니다. 첫째, 1989년 대부분의 동유럽 사회주의 체제와는 달리 북한에는 엄청난 수의 병력으로 구성된 강력한 독립 군대가 있었고 영토 내에는 외국 군대는 없었습니다. 둘째, 북한은 공산주의 국가였을 뿐 아니라 반식민 또는 반제국주의 국가를 표방해왔고, 1960년대 이래로 통치 체제에는 민족 고유 정서 및 민족주의적 요소가 특히 강했습니다. 셋째, 동서독과는 달리 남북한은 서로를 상대로 전쟁을 치렀기 때문에 관계는 매우 달라졌고 갈등 해소는 굉장히 어려웠습니다. 한학자 정인보가 60년 전 미국인들에게 전한 것과 같이 한국, 중국, 베트남 내의 아시아 공산주의는 반식민 민족주의의 피로 발전하였고, 이것이 바로 북한, 중국, 베트남 내의 공산 정부가 권력을 유지할 수 있었던 근본적인 이유입니다.

미국 기업 연구소(American Enterprise Institute)의 닉 에버쉬타트는 1990년 6월 25일 월스트리트 저널에 "북한 붕괴의 도래"라는 제하의 논평을 시작으로 지난 18년간 정확히 이와 같은 퇴보적 예견으로 유명해졌습니다. 그러나 그는 혼자가 아니었습니다. 사실 이는 세 정부를 거치면서 형성된 워싱턴 정가의 공통 생각이었습니다. 지금까지 북한은 붕괴하지 않았고, 따라서 저의 북한에 대한 의견은 옳았던 것 같습니다. 하지만 역사라는 것은 모두가 원하는 믿음 반하는 법이지요. 그래서 바로 헤겔이 역사의 간계를 집필했던 것입니다. 중요한 점은 김 전 대통령의 정책은 이러한 현실을 효과적으로 반영하고 있다는 점입니다. '베를린 장벽이 붕괴된 지 9년이 지났고, 북한은 무너지지 않았습니다. 북한은 "있는 그대로" 다루어야 합니다.’라고 천명하고 있습니다. 1998-99년 미국 대북 정책에 대한 중대한 재평가 실시 이후, 이러한 과정에 대해 윌리엄 페리의 보고서도 같은 점을 지적하고 있습니다.

현실주의의 두 번째 요소는 바로 다음과 같습니다. 김대중 전 대통령은 미국 정부가 북한과 적대적인 관계가 아니라 포용 관계를 추구한다면 북한은 주한미군의 지속 주둔을 반대하지 않을 것으로 생각하게 되었습니다(미군은 남한의 우수한 무장병력이 북한을 삼키지 않고 일본과 중국과의 거리를 유지하게 하면서 DMZ 등 군사분계선 경비에 유용할 것이라는 생각). 정상회의에서 김정일 위원장은 김대중 전 대통령에게 직접적으로 자신은 주한미군의 지속적인 주둔을 꼭 반대하지는 않는 다는 뜻을 밝힘으로써 앞서 말한 견해를 확인시켜 주었습니다. 필요한 것은 남북한 사이에서 "성실한 브로커"의 역할을 해주는 미국이라고 밝혔습니다.

이러한 맥락에서 김 전 대통령의 제안들은 50년 만에 현존하는 동북아 안보체제 내에서 남북한의 화해를 일궈낸 최초의 진정한 시도가 되었습니다. 두 정상은 통일 이후에도 미국의 안보약속을 확보할 수 있는 방법을 구상하여 (국방부 장관 윌리엄 코헨은 1998년 6월, 미국은 한반도 통일 이후에도 미군 주둔을 원한다고 말했다), 중국과 일본의 힘의 균형을 유지하고자 하였습니다. 한반도에서 미군 철수를 조건화 하지 않으면 남북한의 화해는 한반도 내의 긴장과 불안정성의 상당한 감소로 이어지는 동시에 미국은 중국을 봉쇄 혹은 어느 정도 고립시킬 수도 있고, 일본의 강력한 자주 국방력 증강 활동을 막을 수도 있게 됩니다.

저는 주한 미군 주둔을 오랫동안 반대해왔고, 여기에는 크게 두 가지 이유가 있습니다. 첫째, 미군은 1961년부터 대한민국을 곤란에 빠트린 군사 독재를 불가피하게 지지했었습니다. 둘째, 미군의 주둔으로 인해 남북한 관계에서 진정한 변화가 불가능했습니다. 그러나 대한민국은 현재 민주주의 국가이며 햇볕 정책은 성공적이었고 미국은 북한과 다각적인 대화 채널을 열었습니다. 이제 남북한의 한국인들은 미국을 중국, 러시아, 일본을 상대로 한국 안보를 보장하는 역할을 수행한다고 볼 수 있습니다. 물론 이는 옳고 그름을 가릴 수 있는 문제가 아니라 현재 상황이 끊임없는 갈등과 분열이라는 냉전 정책보다 더 나은 것인지에 대한 판단의 문제입니다. 제가 볼 때는 냉전 정책 보다는 훨씬 낫다고 판단되며 현실 정치적 견해로 볼 때 한국과 미국의 안보 우려를 모두 해소할 수 있는 안보 전략이기도 합니다. 또한 안보 구조에 큰 변화를 가하지 않고 통일 한국을 구상하고 수용할 수도 있는 전략입니다. 기존의 남한 또는 미국 정책에서는 생각할 수 없는 부분입니다. 한국인들이 앞으로도 수십 년 간 미군주둔을 원하는지는 별개의 문제입니다만, 이는 한국 국민들이 결정할 문제입니다. 어떤 경우라도 이 두 가지 원리는 종종 순진한 전략이라고 격하된 "햇볕"이라는 현실 정치의 중심을 구성합니다.

반미 혹은 반부시즘?

김대중 정부와 클린턴 행정부가 이뤄낸 대북 정책의 급격한 변화는 2001년 조지 부시 대통령 취임 단 몇 주 만에 즉각적인 도전을 받았습니다. 7년이 지난 지금, 이 명박 정부는 대한민국과 미국 사이에 불화의 위기가 발생했고 이는 김대중, 노무현 전 대통령의 과오로 보는 듯 합니다. 따라서 새 행정부로써 대미 관계를 개선해야 한다고 판단한 것으로 보입니다. 부시 행정부의 생각도 다르지 않은 것 같습니다. 2001년 3월 부시 대통령이 김대중 전 대통령을 소홀히 접견했던 것과는 정반대로 이명박 대통령을 캠프 데이비드 대통령 별장에 초청한 것을 보면 그렇습니다. 이러한 부정적 성향은 마치 한국 국민들이 부시 대통령의 정책이 아니라 미국인 전체에 대해 분노한 것처럼 왜곡돼 대부분 언제나 "반미 감정"으로 낙인이 찍혔습니다. 그러나 사실 조사를 해보면 이는 반 부시즘라는 점이 분명해집니다.

퓨, 갤럽 및 여러 한국 내 여론 조사를 살펴보면 미국에 대한 비우호적 견해는 2001년 1월 부시 정부의 출범, 특히 2002년 초 "악의 축" 연설 그리고 2002년 6월 미군 장갑차 사고로 희생된 두 소녀의 사망 사건 이후 한결같이 갑작스런 상승을 보여주고 있습니다. 이에 수반된 수많은 집회와 촛불 시위는 2002년 12월 노무현 대통령 당선이라는 놀라운 결과로 이어졌습니다. 미국에 대한 비판적 견해는 노무현 대통령의 민주당이 2004년 국회에서 과반수의 의석을 얻는데 일조하였습니다. 그러나 이러한 "반미" 감정이 팽배한 가운데서도, 한국인 30% 정도는 지속적으로 미국 이민을 희망했습니다. 2003년 여론 조사에서는 대학생의 ("반미" 주창자들로 생각되는) 45%가 한국 시민권을 포기하고 미국 시민권을 선택하고 싶다고 답했습니다.

반대로 1990년대 초반에는 거의 70%의 한국 국민이 미국에 대해 우호적인 견해를 나타냈고 15%만이 분명히 부정적이었습니다. 1994년 6월 북한과의 위기 상황으로 인해 이 수치는 57%로 하락했지만 1997년 경제 위기가 있기 전까지 (이것 역시 반 워싱턴 감정을 잠시 일으켰다) 이전 수준으로 상승하였습니다. 2001년 포토맥 협회 연구에 따르면 한국인 59%는 미국에 대해 긍정적이거나 (47%) 매우 긍정적이었고 (12%), 31%는 긍정적이지도 부정적이지도 않았으며, 10%만이 "약간 부정적"이었고 "매우 부정적"으로 조사된 응답은 없었습니다.

포토맥 협회의 윌리엄 왓츠에 따르면 부시 정권이 들어선 뒤 이러한 태도는 완전히 반전되어, 53% 정도의 응답자는 약간 또는 매우 우호적인 성향을 유지했으나, 43%는 약간 또는 매우 비우호적이라고 응답했습니다. 갤럽 코리아에 따르면 20대 한국인 중 22%만이 약간 또는 매우 우호적이라고 응답하였고, 76%는 약간 또는 매우 비우호적이라고 응답했습니다. 과반수가 넘는 응답자 (66%)가 주한미군 철수를 원한다고 답한 연령대도 20대뿐이었다. 2002년 후반 갤럽 코리아의 조사에서는 미국에 대한 대다수의 부정적 견해가 한국인의 모든 계층과 연령층에서 나타났고 미국에 대한 신뢰도는 극적으로 감소했다는 점이 드러났습니다. 퓨 글로벌 태도 조사에서는 2003년 5월 한국인 50%가 미국에 대한 비우호적 견해를 가지고 있으며, 젊은 연령층 중 18-29세 응답자의 71%가 비우호적 견해를 가진 것으로 조사되었습니다. 더욱 놀라운 사실은 미국에 대한 비우호적 견해를 가진 이들 중 72%가 미국 정책에 대한 반대가 아닌 "미국에 대한 일반적 반감"을 표현했다고 퓨가 판단했다는 점입니다. (이는 오랫동안 부정적 태도가 고착화되었다는 점을 암시할 수도 있고 또는 일시적인 상황일 수도 있습니다). 물론 이 때문에 한국이 다른 미국 동맹국 또는 우방국들과 차별화되는 것이 아닙니다. 같은 기간 미국에 대한 우호적 감정이 독일에서는 78%에서 45%, 프랑스에서는 62%에서 43%로 하락했고, 터키에서는 52%에서 15%로 급감했습니다. 그러나 미국은 여전히 일본보다는 신임을 얻고 있었습니다.

반 부시 견해의 증가 원인의 대부분은 다음과 같습니다. (1) 대북 정책에 대한 급격한 미 정부의 정책 변화 (2) 1998년에서 2008년 초까지 대한민국의 햇볕 정책 고수 (3) 남북한 사이에 전쟁이 발발할 수도 있다는 불안감 등입니다. 한국 정부가 북한과의 화해를 심화해 나갈 때, 워싱턴은 정반대 방향으로 움직였습니다. 즉 처음에는 시류에 편승하더니 (클린턴) 갑자기 하차해버린 것입니다 (부시). "테러와의 전쟁"과 이라크 침공은 다양한 이유로 한국 정부와의 긴장감을 고조시켰는데, 미군이 한국에서 이라크로 이동할 때 적절한 협의가 부족했다는 점과 중국이 결부될 수 있는 지역적 충돌에 있어 주한 미군을 사용하겠다는 새로운 정책 등이 그 이유에 포함됩니다. 이러한 것들과 다른 여러 가지 이유로 인해 서울과 워싱턴은 역사상 가장 소원한 관계가 되어버렸습니다. 이는 분명히 워싱턴의 급격한 정책 변화로 인한 것입니다.

부시즘

2002년 후반기에 이르러 발생했던 세 가지 결정적인 순간을 평가해본다면 한미 관계의 이러한 수난에 대한 이해가 더욱 분명해집니다. 9월 국가 안보 위원회의 선제공격 원칙 공표하였고, 10월 제임스 켈리가 (미 국무부 차관보) 평양을 방문해 북한이 제2차 핵 프로그램을 보유하고 있다고 고발하였고, 12월 노무현 대통령 당선이 그것입니다. 선제공격 전략은 -이후 "부시 정책"으로 불림- 한국 정부의 승인이나 지지 없이도 2차 한국 전쟁이 발발할 수도 있다는 가능성을 제기하였습니다. 두 번째 사건은 에서는 북한이 한 두개의 핵무기를 소유하고 있다는 CIA의 오랜 추정 외에 5-6개의 원자탄 존재라는 억측까지 붙어 워싱턴과 평양 관계는 장기적이고 해결이 요원한 또 한번의 답보상태의 시작을 알리고 있었습니다. 마지막 변화로 인해 대한민국 역사상 미국과의 관계를 전혀 경험해보지 못한 대통령의 시대가 시작되었습니다.

한국 지도자들이 즉각 감지했던 한국의 갑작스런 위험은 부시 독트린이란 것이 북한이 촉발한 위기 상황에서 핵 선점을 위한 현존 계획과 부시가 좋아하지 않는 정권은 선제공격 하겠다는 그의 열망이 합쳐진 결과물이라는 것이었습니다. 핵 선점 계획은 수십 년 간 존속 되어온 미군의 표준 작전 절차였습니다. 한국 주둔 미 사령관들은 선제공격과 반 선제공격을 하다가 우발적으로 발발할 수 있는 전쟁에 대해 오랫동안 우려해왔으며 한국에서 퇴역한 사령관들은 개인적으로 새로운 부시 독트린에 두려움을 드러냈습니다. 새로운 독트린이 공표된 몇 달 뒤, 노 전 대통령의 측근 고문이 부시 행정부 관리들에게 미국이 남한의 반대에도 북한을 공격한다면 한미 동맹이 와해될 것이라고 말했습니다. 한국 정부 지도자들은 한국 정부의 반대에도 불구하고 또는 긴밀한 협의 없이는 절대로 북한을 공격하지 않을 것이라는 답을 재차 미 정부에 요구하고 확인하고자 했습니다. (저는 노무현 정부가 이에 대한 확답을 받지 못했다고 알고 있습니다). 북한은 서울 북쪽 산에 배치해 둔 10,000 여대의 화기로 단 몇 시간 내에 서울을 파괴할 수 있기 때문에 부시 독트린이 한국 내에 야기했던 그 엄청난 두려움을 상상할 수 있으실 것입니다. 이 난국은 도널드 럼스펠드가 어떠한 사전 협의 없이 9,000명의 미군병력을 한국에서 이라크로 이동시킨다는 결정과 엄청난 용산 미군 기지를 위험 경로를 피해 한강 남쪽으로 이동하기로 결론이 내려지면서 더욱 악화되었습니다. 2003년 8월 제가 서울을 방문했을 때 한 고위 공직자는 두 군대간의 사이가 이렇게 악화된 적이 없었다고 말했습니다.

저는 2002년 10월 부시 정부가 북한에 제 2차 핵무기 프로그램이 있고 고농축 우라늄(HEU)를 사용한다는 주장의 근거가 된 정보에 의혹을 가졌었습니다. 그러나 제임스 켈리가 평양에서 돌아온 직후 워싱턴에서 열렸던 북한에 대한 대학 학술회의에 참시 참석했을 때 양당에서 파견된 전문가 그룹은 (대다수가 클린턴 정부 출신이다) 정보는 확실하며, "정보기관들"도 HEU프로그램이 가장 우려가 되는 부분이라는 것에 의견일치를 보았다며 모두에게 확신시켰습니다. 그들은 북한이 파키스탄의 핵 과학자 A. Q. 칸 덕분에 별 노력을 들이지 않고 우라늄 폭탄을 생산해낼 수 있는 HEU 원심분리기를 사들여 가동하고 있다고 말했습니다.

이미 보다시피, 북한의 HEU에 대한 미국의 정보는 사담 후세인의 대량학살무기 (WMD)에 대한 정보보다 나은 것도 없었고, 진위를 밝히는 데 미국 정부는 5년을 소비했습니다. 2007년 2월 13일 이뤄진 미국과 북한의 합의 이후 즉각, 정보부 관료인 조세프 디트라니는 상원 위원회에 정보국은 이제 북한의 HEU 무기 프로그램 보고에 대해 "중간 정도 수준의 신뢰도"를 갖고 있다고 보고하였습니다. 이 말은 정보전문용어로 여러 해석이 가능하거나 완전히 증명할 수 없다는 말입니다. 평양은 실제로 수천 개의 알루미늄 튜브를 구매해왔지만 원심분리기의 고속 로터에 활용하기에는 강도가 충분하지 않다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다. 이러한 소소한 구매의 증거는 워싱턴 분석 전문가에 의해 2002년 "상당한 생산 능력"으로 가공되었습니다. 이후, 미국은 HEU 핵 프로그램에 필요한 "대규모 군수품 조달"에 대한 어떤 증거도 내놓지 못했습니다. 일부 공직자들은 북한의 HEU 프로그램 개발 수준은 알 수 없다라고 했습니다. 파키스탄으로부터 원심분리기를 수입했지만 -생산 목적으로는 수천 개가 필요한데, 겨우 20개 정도인 것으로 보입니다.- 그 이후 어떤 일이 행해졌는지는 아무도 모릅니다. 그래서 이제 아까 언급했던 정보기관의 "의견 일치"는 "HEU 수수께끼"로 남게 되었습니다.

결국 김대중과 클린턴이 옳았다고 인정한 부시

2002년 발생한 사건들을 살펴보면 2007년 2월 13일 비핵화 합의로 구현된 조지 부시와 김정일의 따뜻한 관계를 아무도 예측하지 못했을 것입니다. - 하나의 분수령으로써 그 기원은 잘 알 수 없습니다만. 여러분들은 평양이 2006년 장거리 대포동 2 미사일 한 대와 중거리 로켓을 포함한 총 7대의 미사일을 쏘아 올리며 미국의 독립 기념일을 경축했고, 이어 10월 첫 번째 핵실험을 강행했다는 사실을 기억할 것입니다. 이로 인해 북한의 오랜 동맹국인 러시아와 중국이 최초로 UN의 제재 조치에 동의했습니다. (물론 UN의 제7 장 제재 조치는 러시아와 중국이 군사력 지원을 받는다는 것이 표시 나지 않음을 확신하고서야 통과되었습니다)

우리는 부시가 "나쁜 행동에는 보상하지 않는다"며 북한과의 직접 대화를 거부하고 북한을 "악의 축"으로 치부했음을 기억합니다. 또한 다양하게 김정일에 대한 모욕적인 언사를 일삼고 ("피그미 (난쟁이)") 워싱턴포스트의 내부 보도 기자 밥 우드워드에게 자신은 김정일이 지긋지긋하고 북한 체제를 붕괴시키고 싶다고 말한 바도 있습니다. 2004년 딕 체니 부통령은 "우리는 악과 타협하지 않는다"며 다만 "패배시킨다"라고 단언하였습니다. 그러나 크리스토퍼 힐 미 국무부 차관보와 김계관 북한 외무성 부상이 베이징과 베를린에서 가진 직접 비밀 회담을 통해 2월 합의가 도출되었고, 6자 회담에서 비준 받기 위해 상정되었습니다. (중국이 후원한 듯한 형식은 항상 미국과 북한의 대화를 이끌어 내기 위한 제스처였습니다).

이번 합의의 미래지향적인 특징은 다음과 같은 성과목록을 보면 알 수 있습니다. 북한의 플루토늄 원자로의 일시 중지, 무력화 및 해체, 미국 정부가 수 십년간 북한에 가해온 제제와 봉쇄 조치 완화, 미 국무부의 테러지원국가 명단에서 북한 제외, UN 핵 사찰 재수용, 한국 전쟁 종식을 위한 평화 협정, 관계 정상화 노력 등입니다. 이 모든 사항들은 부시 대통령이 취임했을 당시 완성되었거나 협상 중이었던 사항들이기는 했지만, 클린턴 정부 역시 간접적으로 북한의 중장거리 미사일을 돈을 주고 포기시키기 위한 계획을 진행했었습니다. 사실 이 계획은 2000년 서명 준비 상태였으나, 부시 대통령의 결단력 부족으로 성사되지 못했고, 오늘날 북한은 가공할만한 미사일 성능을 보유하게 되었습니다.

조지 부시 대통령이 김정일 위원장과의 정상회담을 가질 가능성까지 만들 정도로 (이 시기 워싱턴 가십에 따르면) 북한과의 협상 타결을 원했던 이유는 무엇일까요? 분명히 2006년 의회 선거는 신세기의 공화당 욱일승천이라는 부시의 존엄한 희망에 치명상을 입혔고 그는 최악의 레임덕 대통령이 되고 말았습니다. 국내외 핵심 지지 기반은 사라져 버렸습니다. 폴 울프비츠, 존 볼튼으로 대변되는 신보수주의자 대다수가 떠났고, 곧이어 토니 블레어와 아베 신조 총리도 물러났으며, 새로이 힘이 강화된 미 국무부와 (그리고 사이가 좋지 못한 부통령과) 남게 되었습니다. 물론 북한이 협상에 응한 이유도 의문입니다. 2006년 후반 저는 북한의 전략은 핵보유국으로서 향후 2년 동안의 제재조치를 겪어낸 다음 차기 미 대통령과 협상을 해보겠다는 것으로 생각했습니다. 크리스토퍼 힐 차관이 북한 협상을 자유로이 관리할 수 있는 권한을 갖게 되면서 뭔가가 평양이 아니라 워싱턴에서 발생했습니다.

가장 신빙성 있는 설명은 부시의 정치적 입지 약화, 신 보수주의자의 퇴거, 혹은 내부 분열의 갑작스러운 종식이 아니라, 이란이 더 큰 핵무기 확산의 위협이라는 판단입니다. 리비아와 같은 거래를 주고받는 외교를 통해 북한과 이뤄질 수 있었다면, 그런 거래는 이란에 엄청난 압력을 가함으로써 협상을 통해 이란의 핵 프로그램 제거할 수 있도록 해볼 수도 있을 것입니다. 부시 대통령이 이란을 상대로 무력을 사용하기로 결정했다면 (2007년 후반 새로운 추정 정보가 등장할 때까지 워싱턴에서 우세했던 소문이었습니다), 북한은 무력화되든지 아니면 단순히 잊혀져야 했습니다. 여기서 무엇이 진실인지 알 수는 없지만 분명히 볼튼과 같은 우익보수주의자들은 아직도 북한과 이란 둘 다 아무 소리 못하도록 제거하고 싶어 합니다. 어떤 경우에든 영변 원자로는 다시 냉각되고 부분적으로 해체되었습니다. 결국 그리 되어야 한다는 의미에서 주요 성과라고 할 수 있고, 북한이 핵 프로그램을 포기할지, 워싱턴이 평양과의 관계를 정상화할지는 지켜보아야 하겠습니다.

과거에서 미래로 - 중국이 근접해 있다.

지난 7년은 기막힌 광경의 연속이었습니다. 미국 대통령이 북한의 수장을 이리저리 모욕하고 근거도 부족한 증거를 가지고 새로운 핵 프로그램 이라며 제재 조치를 취하고, 북한을 악의 축으로 비난하고, 보좌관들은 대북 전쟁 운운하며 협박을 공공연하게 언급하였습니다. 그러는 와중 실제로 북한이 UN 핵 사찰단을 쫓아내고 핵무기를 제조하고 원자 폭탄과 미사일을 실험하는 데는 거의 조치를 취하지 못했습니다. 즉 북한은 전 세계를 자극하는 데 성공함과 동시에, 미국, 중국, 러시아 에 굴복하지 않겠다는 의지(북한 강경론자들이 분명히 원하는 바입니다)를 보여주었습니다. 그런데 갑자기 양자 모두 극단적 입장을 철회하고 클린턴 시대의 주고받는 외교 방식으로 선회한 것입니다. 만약 북한이 승리했고, 그들이 원하는 것을 챙겼다고 본다면, 우습게도 이는 10년 전 북한이 스스로 하겠다고 한 약속을 어려운 과정을 통해 얻어냈다는 것 밖에 다른 의미는 없습니다. 당시 북한은 핵 프로그램을 경제원조와 교환하고 미국과의 관계를 정상화하겠다고 하였습니다. 하지만 워싱턴 정가와 부시 행정부의 신보수주의자들은 그 약속을 부정하고 조소하였습니다.

1990년 후반 성공적 외교는 근본적으로 노벨 평화상 수상자인 김대중 대통령이 이끌었습니다. 김 전대통령은 결국 평양이 미국과의 새로운 관계 정립을 위해 핵 프로그램과 미사일을 포기할 것이라고 빌 클린턴을 설득하였습니다. 김 전 대통령의 생각에 이는 미국에게 일거양득의 기회였습니다. 왜냐하면 미국이 북한과의 관계를 정상화했다면 북한도 주한미군 지속 주둔을 반대하지 않았을 것이기 때문입니다. 미국 정부는 친구도 아니고 동맹도 아니지만 위협이 되지 않는 북한을 얻을 수 있었습니다. 중국과 부활한 러시아에 대응할 수도 있고 일본의 향후 진로에 대한 견제책으로도 북한을 활용할 수 있었습니다. 클린턴의 가까운 동지였지만 미국 대통령 예비 선거에서 중요한 시점에 바락 오바마를 극적으로 지지하고 나선 빌 리처드슨은 2007년 4월 북한을 돌아보고 북한은 스스로 "미국의 궁극적 동맹국"으로 보고 있다고 보고했습니다. 다시 말해 "대중국용 동맹국"이라는 말이었습니다. 북한은 스스로 "미국과 중국 사이의 전략적 완충 역할"을 하고 있는 것으로 생각한다는 것입니다. (북한은 오랜 냉전 기간동안 소련과 중국 사이에서 그랬던 것처럼 미국과 중국 사이의 긴장에서 이득을 취하려 할 가능성이 높습니다)

이러한 새로운 사고방식이 부시 대통령에게 영향력을 발휘했는지 알 수 없지만 2007 정상회담이 우리 시대의 새로운 정치 경제 지도를 그렸던 것처럼 새로운 사고방식은 21세기 동북아를 겨냥한 논리적인 미국의 전략입니다. 어찌됐든 알 수 없는 일련의 사건으로 말미암아 조지 부시 대통령은 2002-2006년까지 펼쳤던 자신의 대북 정책이 아닌 김대중 전 대통령의 햇볕 정책에 가까운 가까워졌습니다. 그가 백악관을 떠나기 전 심지어 "악을 행하는" 김정일과 악수를 나눌지도 모를 일입니다. 정말 그렇게 된다면, 글쎄요, 하지 않는 것보다는 늦어도 하는 것이 나은 법이죠.

A major purpose of this conference is to take stock of the June 2000 summit with the benefit of eight years of hindsight, also to examine the achievements of the October 2007 summit, and to assess where we are today in relations with North Korea. My perspective is obviously an American one, and I am deeply interested in where Korean affairs might go after the inauguration of a new American president only eight months from now. But I am afraid I sometimes overestimate American influence on Korean affairs. I think recent years have demonstrated that when Korean leaders want something badly enough, and stick to their policies and principles, they can directly or indirectly influence American leaders toward adopting similar policies. And so I want to make one major point that I will come back to in the end: Presidents Kim Dae Jung and Roh Moo Hyun persisted with their engagement policy toward Pyongyang through five years of intense American pressure, criticism, and provocation, and ultimately were vindicated when the Bush administration turned 180 degrees and also adopted an engagement policy. Why this happened is still something of a mystery, but it certainly did happen.

Today we also have the spectacle of a new Korean administration trying to cozy up to the United States by invoking a hard line on North Korea, even as President Bush himself has given up that hard line, and talking about "ten lost years" as if this will sound good in Washington, but without a lot of apparent thought given to Bush’s unpopularity (the lowest rating of any president since modern polling began), or the likelihood that the next American president will not be a Republican. This will sound like a partisan statement, but sometimes one political leader has a grip on realities and another one does not, and I think this is one of those cases. Everywhere else in the world people are counting the days until this failed Bush administration leaves Washington-but not in the Blue House.

The 2000 Summit

We are here to commemorate President Kim Dae Jung’s far-reaching changes in North Korea policy that culminated in the Pyongyang Summit of June 2000, where the two Korean heads of state shook hands for the first time since the country’s division in 1945. In my judgment as an historian President Kim did more to change policy toward the North than any previous South Korean or American president, in spite of Seoul facing a far greater immediate threat than anyone else. At his inauguration in February 1998 President Kim pledged to "actively pursue reconciliation and cooperation" with North Korea, and declared his support for Pyongyang’s attempts to better relations with Washington and Tokyo-in complete contrast with his predecessors, who chafed mightily at any hint of such rapprochement. Kim Dae Jung explicitly rejected "unification by absorption" (which was the de facto policy of his predecessors), and in effect committed Seoul to a prolonged period of peaceful coexistence, with reunification put off for twenty or thirty more years. He became the first Korean president to call for an end to the many American economic embargos against the North in June 1998, during a visit to Washington.

North Korea waited a year to test Kim Dae Jung’s resolve, and a couple of submarines and several dead infiltrators washed up on the South Korean coast-suggesting that hardliners might be trying to disrupt North-South relations. But by mid-1999 it was apparent that Pyongyang viewed President Kim’s "sunshine policy" as a major change in South Korea’s position. Its attitude toward Washington also began changing. Long determined to get the U.S. out of Korea, it appeared that at least some North Korean leaders want American troops to stay on the peninsula, to deal with changed international power relations (especially a strong Japan and a strong China), and to help Pyongyang through its current economic difficulties.

The Sunshine Policy came from President Kim’s long study of the North-South problem, and from a recognition that NK wouldn’t collapse and therefore had to be dealt with "as it is," rather than as we would like it to be. One of the few virtues of getting older is to see whether one's predictions are any good or not. Since the East European regimes fell in 1989-90, many experts have predicted the collapse of North Korea. Since that time I have argued that North Korea will not collapse for three reasons: (1) the primary reason is its independent army of great numerical strength, and the absence of foreign troops on its territory-unlike most of the East European communist regimes in 1989; (2) because the North has always been an anti-colonial or anti-imperial nationalist entity as well as a communist state, and the indigenous or Korean nationalist elements of the regime have been particularly strong since the 1960s; and (3) because the two Koreas fought a war against each other, unlike the two Germanys, and this makes their relations very different, and makes the conflicts between them very hard to resolve. Asian communism in Korea, China and Vietnam was fertilized with the blood of anti-colonial nationalism, as the literateur Chong In-bo often told American 60 years ago, and that is the basic reason why the Asian communist governments of North Korea, China and Vietnam remain in power.

Nick Eberstadt of the American Enterprise Institute has distinguished himself by getting this exactly backwards for the past eighteen years, ever since his June 25, 1990 Wall Street Journal editorial titled "The Coming Collapse of North Korea." But he is hardly alone: this has been a Beltway consensus through three administrations. So far the North has not collapsed, and so I must have been right about North Korea. But history has a way of contradicting everyone's favorite beliefs; that’s why Hegel wrote of the cunning of history. The point is that President Kim’s policy effectively dealt with this reality: nine years after the Berlin Wall fell, the North had not collapsed, and had to be dealt with "as it is." After a major reevaluation of U.S. policy toward the North in 1998-99, William Perry’s report on this process said the same thing.

A second element of realism was this: Kim Dae Jung came to believe that North Korea does not oppose a continuing U.S. troop presence in Korea if Washington were to pursue engagement with Pyongyang rather than confrontation (U.S. troops would continue to be useful in policing the border, i.e. the DMZ, in assuring that the South’s superior armed forces don’t swallow the North, and in keeping Japan and China at bay). At the summit Kim Jong Il confirmed this view, telling Kim Dae Jung directly that he did not necessarily oppose the continuing stationing of U.S. troops in Korea-what is required is for the US to play the role of "honest broker" between the two Koreas.

In this sense, President Kim’s proposals constituted the first serious attempt in 50 years to achieve North-South reconciliation within the existing Northeast Asian security structure. They also envisioned a way for the U.S. to retain its security commitment even after unification (Secretary of Defense William Cohen said in June 1998 that the U.S. wanted to keep troops in Korea after unification), and thus maintain a balance of power between China and Japan. Reconciliation between the two Koreas without requiring the US to remove its troops from the peninsula would lead to a big reduction in the tensions and volatility of the Korean peninsula, while enabling the U.S. to continue a modest encirclement or containment of China, and to keep Japan from developing a strong and independent military force.

I have been a critic of the stationing of American troops in Korea for many years, mainly for two reasons: first because those forces inevitably supported the military dictatorships that afflicted the ROK from 1961 onward, and second because the presence of these troops made any real change in North-South relations impossible. But the ROK is now a democracy, the Sunshine Policy has been successful, the US opened many-sided talks with the North, and so Koreans in both South and North can look upon the U.S. as a guarantor of Korean security vis-a-vis China, Russia and Japan. Anyway, this is not a question of right and wrong, but a question of whether the current situation is preferable to the endless conflicts and divisions of Cold War policy--and I think it clearly is much more preferable, and from a realpolitik standpoint, this is a security strategy that works to satisfy both American and Korean security concerns. It is also a strategy that could envision or accommodate a reunified Korea without requiring major changes in security structures. We could not say that about previous South Korean or American policies. Whether Koreans will want American troops to remain for many more decades is another question, of course, but it is a question for Koreans to decide. In any case, these two principles constitute the realpolitik core of "sunshine," a strategy often derided as naïve.

Anti-Americanism or Anti-Bushism?

The sharp changes in North Korea policy accomplished by Kim Dae Jung and the Clinton administration were immediately challenged by George W. Bush, within weeks of his inauguration in 2001. Seven years later, the Lee Myung Bak administration appears to think that a daunting rupture occurred between the ROK and the U.S., and that it was the fault of Kim Dae Jung and Roh Moo Hyun-thus requiring the new administration to repair relations with Washington. The Bush administration seemed to think so, too, by inviting President Lee to the presidential retreat at Camp David-in total contrast to the disastrous reception Bush gave to Kim Dae Jung in March 2001. This negative tendency is almost always labeled "anti-Americanism," as if Koreans were upset about Americans in general, rather than Bush’s policies in particular. But when we examine the evidence, it is quite clearly anti-Bushism.

Pew, Gallup, and domestic Korean polls uniformly show a sharp spike in unfavorable views of the United States, clearly dating from the advent of the Bush Administration in January 2001 and especially the "axis of evil" address in early 2002, and the deaths of two young girls when they were accidentally run over by a US military vehicle in June 2002. Many subsequent demonstrations and candle-light vigils led up to the surprise election of Roh Moo Hyun in December 2002. Critical views of the U.S. also helped his party win a majority in the National Assembly in 2004. But amid this "anti-Americanism," some 30 percent of the Korean population continued to express a desire to emigrate to the US, and in a 2003 poll fully 45 percent of college students (presumed to be the vanguard of "anti-Americanism") said they would choose American citizenship over Korean citizenship.

In the early 1990s, by contrast, nearly 70% of Koreans polled held favorable views of the US, and only about 15% were clearly negative. In 1994 this figure ped to 57%, largely because of the June 1994 crisis with North Korea, but it returned to previous levels until the 1997 financial crisis (which also led to a brief spike in anti-Washington sentiment). In 2001 a Potomac Associates study found that 59% of Koreans were positive (47%) or very positive (12%) toward the US, 31% were neither positive nor negative, only 10% were "somewhat negative," and none were "very negative."

This orientation underwent "a sea change" after Bush came to power, according to William Watts of Potomac Associates, as 53% remained somewhat or very favorable, but 43% became somewhat or very unfavorable. According to Gallup Korea, among Koreans in their 20s only 22% were somewhat or very favorable, and fully 76% were somewhat or very unfavorable; this was also the only age group in which a majority (66%) wanted US troops to withdraw from Korea. In late 2002 Gallup Korea showed a majority negative view of the US across all classes and ages of Koreans, and dramatically lowered levels of trust in the USA. The Pew Global Attitudes Survey found in May 2003 that 50% of Koreans held an unfavorable view of the US, but among younger groups, fully 71% of those aged 18-29 had unfavorable views. More surprising, Pew determined that among those who had unfavorable views of the US, fully 72% expressed "general hostility toward America" rather than opposition to American policies. (This may suggest a hardening of negative attitudes over time, or it may be a mere blip.) Of course, all this made Korea no different from other American allies and friends: Germany fell from 78% favorable views to 45% during the same period, France went from 62% to 43%, and Turkey collapsed from 52% to 15%. ) Nonetheless, the US was still trusted much more than Japan.

In my view nearly all of the growth in anti-Bushism has come about because of (1) an abrupt shift in Washington’s policies toward the North, (2) continuity in South Korea’s Sunshine Policy from 1998 to early 2008, and (3) fears that South Korea could be drawn into a new war with the North. As Seoul pursued a deepening reconciliation with the North, Washington reacted in opposite ways: first it jumped on that bandwagon (Clinton) and then it abruptly dismounted (Bush). The "war on terror" and the invasion of Iraq provoked deep strains with Seoul for a variety of reasons, including a lack of proper consultation in moving American troops from Korea to Iraq, and a new policy of using US troops stationed in Korea in a regional conflict that might involve China. For these and other reasons the deepest estrangement in history emerged between Seoul and Washington-but it happened because of sharp policy change in Washington.

Bushism

We can understand these difficulties in Korean-American relations better if we examine three defining moments that occurred as the year 2002 drew to a close: the publication of the National Security Council’s preemptive doctrine in September; James Kelly’s visit to Pyongyang in October, where he accused the North of having a second nuclear program; and the election of Roh Moo Hyun in December. The preemptive strategy-later called "the Bush Doctrine"-raised the possibility that a new Korean War could erupt without Seoul’s approval or support; the second signaled the beginning of another long and still unresolved stalemate between Washington and Pyongyang, along with the possible fabrication of five or six atomic bombs in addition to the CIA’s longstanding estimate that the North has one or two weapons; and the last change brought to power the first president in South Korean history with no experience with or attachments to the United States.

The acute danger in Korea-which South Korean leaders immediately grasped-was that the Bush doctrine conflated existing plans for nuclear preemption in a crisis initiated by the North, which have been standard operating procedure for the U.S. military for decades, with Bush’s desire to preemptively attack regimes he does not like. American commanders in the South have long worried about a war accidentally breaking out through a cycle of preemption and counter-preemption, and retired commanders of our forces in Korea were privately appalled by the new doctrine. A few months after the new doctrine became public, a close advisor to President Roh told Bush administration officials that if the U.S. attacked the North over South Korean objections, it would destroy the alliance with the South. Leaders in Seoul repeatedly sought assurances from Washington that the North would not be attacked over Seoul’s objections or without close consultations. (It is my understanding that the Roh Moo Hyun administration did not get those assurances.) Since the North can destroy Seoul in a matter of hours with some 10,000 artillery guns buried in the mountains north of the capital, one can imagine the extreme consternation that the Bush doctrine caused in Seoul. These difficulties were aggravated by Donald Rumsfeld deciding to move 9,000 soldiers from Korea to Iraq, with the barest consultation, and concluding that the huge American base at Yongsan would be moved well south of the Han River, out of harm’s way. When I visited Seoul in August 2003 a prominent official told me that relations between the two militaries had never been worse.

I remember being skeptical of the intelligence behind Bush administration claims in October 2002 that the North now had a second nuclear weapons program, using Highly-Enriched Uranium (HEU). But when I showed up for a university conference on North Korea in Washington shortly after James Kelly returned from Pyongyang, a bipartisan assemblage of experts (many from the Clinton administration) assured everyone that the information was solid, and that an "intelligence community" consensus had emerged that the HEU program was most worrisome. Pyongyang, they said, had gotten on Pakistani arch-proliferator A. Q. Khan’s gravy train, buying and putting in motion a bunch of HEU centrifuges that could yield a uranium bomb.

As it happened U.S. intelligence on the North’s HEU was no better on than it was Saddam Hussein’s WMDs, but it took five years to find that out. In the immediate aftermath of the February 13th, 2007 agreement between Washington and Pyonguag Joseph DeTrani, a longtime intelligence official, informed a Senate committee that intelligence agencies now pegged reports of the North’s HEU weapons program at only "the mid-confidence level," which is jargon for information that can be interpreted in various ways, or isn’t fully corroborated. Pyongyang had indeed purchased thousands of aluminum tubes: but it turned out that these tubes weren’t strong enough to use in the high-speed rotors necessary for centrifuges. Evidence of these modest purchases had been transformed by Washington analysts into "a significant production capability" in 2002; since that time, however, the U.S. had turned up no evidence of the "large-scale procurements" that would be necessary for an HEU bomb program. Other officials said the degree of the North’s progress toward an HEU program was unknown; they did import some centrifuges from Pakistan-a mere twenty of them, as it turned out, when thousands are needed for production purposes-but no one knew what had happened since: so now the intelligence "consensus" had turned into "the HEU riddle."